This year’s Wimbledon champion will receive a winners check for about $3 million. When Tony Trabert won the trophy there in 1955 they gave him a 10-pound note.

“Redeemable at Lilly White’s department store in London,” Trabert recalled last week. “But only in the sports section and only on tennis things.”

Working the TPC for CBS Sports in 1982, Trabert met his future wife Vicki and has lived in Ponte Vedra ever since.

“We met on March 20th, 1982, easy to remember. It’s our zip code, 32082.”

I used to reference Tony Trabert in my television career all the time. “No Americans are left at the French Open,” I would say year after year. “Tony Trabert is the last American to win the French in 1955.” That went on until 1989 when Michael Chang ended the 34-year drought. Jim Courier and Andre Agassi are the only other Americans on the list of winners at Roland Garros in the last 63 years.

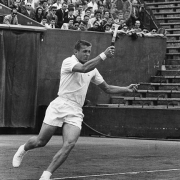

Of the four Grand Slam tournaments, Trabert won everything. Only the singles in Australia and the doubles at Wimbledon eluded him. He made eleven appearances in Grand Slam finals with ten wins.

Trabert’s post-playing career included 31-years with CBS Sports, more than two decades as an analyst with Channel 9 in Australia and an 12-year stint as the President of the International Tennis Hall of Fame, where he’s also a member. He was number one in the world and was on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

But it’s his Wimbledon victory in 1955 that stands as one of his fondest memories. “There’s such tradition involved, the whole thing wreaks with class. Everything is done beautifully. They’re great with the players, They do everything they possibly can.”

“If you ask any tennis player if you could win any of the grand slams, they’d say Wimbledon,” Trabert said last week. “I first played there in 1950, I was so nervous I could hardly breathe.”

“That was the year Bill Talbert took me to Europe. I was nineteen. We won every tournament we played in. Italian, French. Talbert said he owed it to Gardner Malloy, his regular doubles partner to play with him at Wimbledon. I partnered with Budge Patty. Budge won the singles and we lost in the semi’s in the doubles. One set was 31-29 in the quarterfinals. They wouldn’t let us replace the balls. We got to 20 all and I said to the umpire, “Any chance to replace the balls?” He said, ‘It’s against the rules.’ I asked if we could use the balls we used in the first set. He said no. So I said, “What if I hit these out of the stadium? They got the referee and we used the balls in the first set.

“We only played one match that day instead of two. That was a Thursday. They used to play the men’s singles Friday and the women’s on Saturday.”

“I thought our doubles match killed Patty but he won the singles over Frank Sedgeman in the finals. We played the doubles semi’s after that and he was cooked.

Just five years later, he was a Wimbledon champion. Of course, 1955 was a pretty magical year for Trabert. He won three legs of the Grand Slam, still only one of a handful of players who have done that. It started in late 1954 with a trip to Australia to play in the finals of the Davis Cup.

Getting there was a chore in itself at the time. Trabert and his playing partner Vic Sexias spent fifty hours of flying time just to get Down Under.

“Five, 10-hour legs with a six-hour stop over in Hawaii,” he recalled. “We knew the pro at the Royal Hawaiian, George Peebles so he set up an exhibition there during our stop. Vic and I played, jumped in the ocean, showered and ran back to the airport for the next leg. I think we got $500 each. Of course that was against the rules.”

“The Davis Cup was as big as any of the majors,” Trabert said “They sold 25,500 tickets and told us later they could have sold 50,000.” It was the largest crowd to ever see a tennis match at the time. “Taxi drivers wouldn’t charge us, they just said, Give me a autograph for my daughter. And I hope our guys beat you blokes.”

“The traffic was so bad our captain Bill Talbert got out of the car and told the policeman at the corner we needed to get to the venue. He jumped on his motorcycle and escorted us down the wrong side of the street to get there.”

Winning the Davis Cup was a VERY big deal, but the Australian Championships were just three weeks away in Adelaide. Trabert had been Down Under for several months and said Ken Rosewall just plain beat him in the semi-finals on his way to the title.

The rest of the year belonged to Trabert.

He was the defending champion at the French where he beat Sven Davidson in four sets to claim the title in back to back years. “He beat me 6-2 in the first set so on the changeover I figured I better start doing something different,” he explained.

From there, Wimbledon was just two weeks away.

Sometimes you wonder if the great players remember how they played in the big moments or if it was just a reaction. Trabert, who will be 88 next month, remembers it all in vivid detail.

“My first match on Centre Court was against Tony Mottram, Britain’s #1 player in 1950,” he remembered. “I lost in straight sets. The net looked higher than a backstop. When I got home to Cincinnati my dad asked me ‘What’d you do after match point?’ I said I shook his hand. Then he showed me the paper (The Cincinnati Enquirer) with a picture of me sprawled out on the grass. I didn’t remember that!”

He does remember every moment of match point against Kurt Neilson on the grass at Centre Court Wimbledon, 63 years ago.

“I served and it went in, like we always did then on grass, volleyed to his forehand. He threw up a high defensive lob, I was hoping it would go out but it landed right on the baseline so I hit a forehand to his forehand that he chipped to my backhand. He came charging in and I hit an offensive backhanded lob over his head. He jumped and realized he couldn’t get to it and he walked to the net to shake hands.”

Doing a little research, I went to the Internet to see if there was any video of that. Sure enough, YouTube had match point and it was EXACTLY as he described 63 years later.

Kurt Neilson got to the final in 1953 and lost to Sexias. In ’55 he beat Rosewall to get to the finals.

Trabert explained his midset after winning the semi-finals at Wimbledon in ’55 and expecting to play Rosewall in the finals. The upset changed his preparation.

“I thought ‘I can’t come out cocky,'” he said. “I thought I was the better player. I was mentally preparing for Rosewall. But Neilson beat him and I had to get emotionally ready to play him. I won without losing a set.

“Neilson said later he thought that year he lost to a better player.”

In Singapore more than 40 years later, Tony and Vicki were buying a rug during a round the world trip. When the stepped out of the store the sidewalk “Was packed and was wide like 5th Avenue,” Tony said. “We’re deciding which way to go and Vicki says, ‘Here’s comes a guy you know from tennis!” I look up and here comes Kurt Neilson. One minute earlier or later and we miss them.”

On his way to the All-England title in ’55, Trabert didn’t drop a set. The same happened at Forest Hills for the U.S. Championships later that year.

“When I was at my best years, the draws were so weak, if I just paid attention I’d make it to the quarterfinals. Now you better be ready on Monday, there’s so much depth.”

“A player like Lew Hoad had more ability than I did,” Trabert explained. “But if he had ups and downs, I could get by him. I played at a high level then and maintained that for two weeks.”

He beat Rosewall in the finals for his third Grand Slam of the year.

It didn’t take long for Trabert, also a starter on the University of Cincinnati basketball team, to adjust to playing on the international stage. He played throughout Europe in 1950 with Talbert, a fellow Cincinnatian, as his doubles partner. Trabert was 19-years old. They won every tournament they played, the Italian and the French Opens included.

A following two-year stint in the Navy limited his playing time but didn’t stop him completely from competition. Assigned to the bridge for “Air Defense” on board the aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea in the Mediterranean, Trabert got liberty to go play in the French in 1952. “I lost in straight sets to Felicisimo Ampon from the Philippines. He got everything back. I hadn’t played enough.” Trabert was back in the US in ’53. He won the French in in 54 and 55.

He signed a professional contract with Jack Kramer in January of 1956, ending his eligibility to play in the Grand Slam tournaments. Before the open era of tennis in 1968, only “amateurs” were eligible for the big four.

Add to a successful playing and broadcasting career a five-year stint as Davis Cup captain that included two wins and an encounter with an apartheid protester on center court. He’s met six Presidents and had a famous life in LA where he counted Frank Sinatra, Charlton Heston and John Wayne as his friends. Still, Wimbledon still remains a highlight.

“It’s the world’s stage; it’s a thrill and a half. Such tradition with the ivy on the walls, and everything’s done so precisely. In those days they picked us up in Bentley’s and drove us on the property. They don’t do that anymore,” he said with a laugh.

So does he remember what happened at the end of the match in ’55?

“I went right by the umpire’s stand and accepted the trophy from the Duchess of Kent,” he recalled. Then we walked off.”

Once he turned pro, Trabert played in a barnstorming tour with Pancho Gonzalez, facing each other 101 times. Gonzalez won 74 with Trabert saying Gonzalez’s serve was the big difference.

“We traveled with a canvas court and put it down with block and tackle. We started at Madison Square Garden but we played on ice rinks, high school gyms, you name it. We drove from town to town in two station wagons.”

“In1960 Jack asked me to go to Paris. and promote pro tennis in Europe, Africa and Asia,” Trabert said of his move overseas. “Philippe Chatrerie turned out to be my best friend. He helped set me up in an apartment right next to the Arch. We were there for three years.”

I told Tony I was headed to Paris a couple of summers ago. I’d be stopping over in the “City of Lights” for just a couple of days.

“There’s a restaurant I want you to try,” he said as he walked to the other room to grab some papers. He came back with a calling card and a map to “Le Relaise de Venise.”

“Go to the Arc (de Triomphe) and walk down the Grand Armee on the other side. It’s on a side street. There will be a line, you can’t miss it.”

As usual, Tony was exactly right, so my wife Linda and I found ourselves waiting in line outside the restaurant the first night we were there with people from all over the world. Since there are no choices on the menu, the line goes pretty quickly no matter how long it is. A well-dressed, French matron of the house who clearly had been in charge there a long time seated us.

Taking a chance, I told our waitress that Tony had sent me there and perhaps the hostess knew him during his time in Paris.

Excitedly, our waitress brought the hostess to our table and said, yes, Madame knows Monsieur Trabert. “His was a beautiful victory,” our waitress translated as Madame talked at tableside. “We must have a photo when you’re finished,” she said as she went back to work.

And sure enough, when Linda and I finished, she came outside and we took some pictures together. In a few she was blowing kisses to Tony in dramatic fashion.

Trabert is the one who signed Rod Laver to a pro contract in 1963. He had just won all four Grand Slam tournaments in ’62.

“It was a coup to have Laver after he won the Grand Slam in 1962,” Tony remembers. “But then he couldn’t play in any of the majors for five years. That’s 20 grand slams. He won 11 Grand Slam tournaments and they stopped him in his prime. He missed twenty of those. Who knows where he’d have put the record.”

There’s a lot of talk about trainers and fitness and coaches and different techniques in tennis these days. Trabert admits the game is different, but not so different that he couldn’t have competed at the top level.

“The top 5 players in any era could have competed in any other era,” he said. “Those top players are good enough to adjust. We worked on fitness, sleep, what we ate. All the majors were best of five, with no tiebreaks. And we played singles and doubles. It wasn’t that demanding to win singles and doubles because of the depth of the fields.”

“The difference today?” he added. “Depth, way more good players playing the game today. The equipment, like golf, has changed how they play the game. And the money has changed dramatically.”

“I don’t particularly like how the game is played now. Just stand at the base line and crush it. We had to set a point up.”

Best player ever? Trabert believes the discussion comes down to two guys.

“Hard to say (Rod) Laver’s not the best ever since nobody’s ever done what he did. (Win the Grand Slam). But it’s also hard to say Federer isn’t the best player ever based on what he’s done against very deep fields for a long time.”

Federer and Rafael Nadal remain at the top of the game and Trabert thinks the world of both of them as players and as people.

They’re fantastic for the sport. Great human beings. They represent their countries; their sport and themselves as well as you can do it. They have so many difficult people to beat in any tournament.”

As the Davis Cup Captain, Trabert got to see a generation of tennis players who didn’t match up with his ideas of grace and sportsmanship.

At the time John McEnroe was the “Bad Boy” of tennis but was also the best player in the world. He loved playing Davis Cup, representing his country and teamed with Peter Fleming to form the #1 doubles team in the world.

Everybody says when you play for your country, it’s different. As the team captain, Trabert imparted that to his players in a small speech. Fleming said, “It’s tennis.”

“So we were playing in Mexico and we’re staying right across the street from the venue. The referee sticks his head in our cubicle and says, ‘You ready?’ And Peter says to me ‘I forgot my rackets.’ I said, ‘Welcome to Davis Cup.’ Vitas (Gerualitis) ran across a six-lane highway. I told him ‘Bring every racket you find.'”

“John acted badly enough,” Trabert recalled of his time with McEnroe. “But John was very coachable, He came for the team meetings, always on time. But I couldn’t control him on the court.”

“Part way through the doubles match vs. Mexico. We had won the first two sets 6-4, 6-4,” he explained. ‘Middle of the third set they broke Fleming and McEnroe blew a service game. So I said on the crossover ‘You gonna be pros or you going to mess around. Fleming said, ‘I’m not going to play for a captain like that.’ So I told them I’d default right there. John did enough things on the court that the spectators knew what was happening. We won the doubles and they were raining down seat cushions. We went to the locker room and the officials said you should sit in here for a while, there are some angry people out there. Congoleum, the flooring company was our big sponsor. We flew on their plane. Their president rolled up his American flag and stuck it in his pocket and said to me, ‘I don’t’ sponsor things I’m not proud of.’ And he didn’t.”

“It’s an international sporting event,” Trabert said of the Davis Cup. “You do the right things, you go to the embassy, you represent the country. John asked me later if he was the cause of the problem and I told him, ‘Yes.'”

McEnroe eventually apologized to his captain years later. Trabert’s tenure as the captain lasted for 5 years from 1976-80. The US won it twice in that span.

He’s also the only Davis Cup captain to ever carry his own racket on the court. In 1977 the US was facing South Africa in Newport Beach, California. There were plenty of apartheid protest going on and law enforcement warned Trabert and the team that it was going to spill over onto the match (in Davis Cup they actually call it a ‘tie’).

“They told us to let them do whatever they were going to do but to defend ourselves if necessary,” he recalled. “I took my racket out on the court just in case and sat it next to my chair. We had a policeman on our floor. They checked everybody’s bags.”

As expected, several protesters disrupted the match.

“A guy had oil in a milk carton and threw it on the court. He bounced right up in front of me. He had something in his hand, and was coming right at me. I popped him three times in the ribs before the cops grabbed him.”

I was watching the French Open finals in 1984 when John McEnroe won the first two sets against Ivan Lendl. It looked like he was on his way to victory and end the American’s drought when he missed an overhead and Trabert said in his role as a TV analyst, “I don’t like what I saw there.” Sure enough, McEnroe faltered and Lendl prevailed in five sets.

I asked Tony last week “Are you the oldest living Wimbledon winner?” “Oh no, I’m like 4th or 5th,” Trabert said quickly. “There’s Vic (Seixas), (Bob) Falkenberg, Dick Savitt, and (Frank) Sedgman.” Sharp as ever. And right.

No story about Trabert fails to mention what a gentleman he is. And that’s very true. He’s a sportsman, true to the definition of the word.

“If a guy beats you, shake his hand and wish him luck,” he’s told me time and again. “And don’t get in a smelling contest with a skunk,” is one of his favorite pieces of advice I’ve heeded.”