Sports Idols

It was easy having sports figures as childhood heroes growing up in Baltimore. At various times as a kid, depending on the season, I was Frank Robinson at the plate, Brooks Robinson at third, and Paul Blair in the outfield. I was Johnny Unitas in my front yard throwing at bushes. Playing catch, I was Lenny Moore flanking out wide or Raymond Berry making a tip-toe sideline catch. During basketball season, as much as I wanted to be Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, because I was the tallest kid on the block, I was always Wes Unseld, trying to perfect the two-hand overhead outlet pass.

Because of my job, I’ve been lucky to meet all of my boyhood heroes. I’ve had a chance to shake their hands and tell them what a positive impact they had on my life as a kid. I caught Chuck Thompson, the Orioles play-by-play announcer in the Baltimore dugout during the ’83 World Series and told him he always made that job sound like fun. I stopped Joe Namath in the lobby at the Marriott at Sawgrass. Even luckier, I was never disappointed by any of them, even sharing a laugh with Namath that he became my idol despite beating the Colts in Super Bowl III.

“Having a hero means you have somebody to look up to and to emulate,” Frank Palmieri, a professional psychotherapist and counselor explained this week. “A lot of times kids are so young they haven’t figured out that they have parents who could be their heroes.”

Palmieri, who idolized the Yankee’s Yogi Berra and Whitey Ford as a kid, also said its easy to have sports heroes when you’re young because they’re removed from reality.

“They’re not making me go to bed, eat my vegetables, and they’re not disciplining me. So, it’s easy to idolize them,” he said.

Having sports heroes as a kid was just a part of life to most of my friends. But when I asked about that this week, I got several different answers. They’ve never met their heroes and sometimes, their heroes showed to be flawed, on and off the field.

“I wanted to be Stan the Man,” Pedro said immediately referencing the St. Louis Cardinals Stan Musial when I asked about his childhood idols. “He was a lefthanded hitting first baseman and I was a lefthanded hitting first baseman, I was going to the Majors to be Stan the Man.”

I knew I was sad when Frank Robinson died two years ago and asked Pedro if he felt the same when Musial died in 2013.

“I was sad, but I thought about what a great life he had,” Pedro said. “But honestly, I thought back to how upset I was as a kid when they moved him from third to sixth in the lineup at the end of his career.”

Palmieri laughed when I told him that story.

“You might be able to figure that out when you’re twenty or thirty, like why they moved Mickey (Mantle) to first base. They did the same thing to DiMaggio, and he didn’t like it,” he said. “But you can’t figure that out as a kid. You don’t realize that they probably extended their careers a few years by doing that. You don’t have the depth of experience.”

“When Yogi and Whitey died, I was sad. But I thought about it as an adult, and I was so glad that I got a chance to see those guys play. They were great examples of excellence at what they were doing.”

When sports idols fall from grace, it can take some sorting out as an adult to take them off that pedestal and bring them down to earth, flawed, like everybody else.

“O.J. was my guy,” my friend Mike said when I asked about his boyhood idols. “I wanted to be O.J. I was a running back, I wanted to wear #32. I tried to be just like him.”

“What did you think when he was on trial for murder?” I asked.

“I just thought, ‘How can you be that kooky?’’ he answered. “I just wanted to say to him, ‘Man, how could you act like that?’”

When Pete Rose got into trouble and was banned from baseball, my friend Billie had to take some time to sort that out.

“I was all about Pete Rose,” he said. “I wanted to hustle like him, play like him. When he got into trouble, I was an adult and I defended him for a while. But as I worked through it, I thought, ‘Hey, that was wrong,’ and I stopped defending him.”

“It’s a positive thing, even into adulthood. Especially when you’re emulating somebody who doesn’t fall from grace,” Palmieri noted about having a sports idol.

“I looked at Mickey in my work and I was able to say professionally he had a problem. Mickey even said, ‘Don’t be like me,’ at the end of his life, realizing that he had his own failings. You see them as human beings, having the same faults and failings that you might have.”

Being on the other side of the equation can be just as baffling. Just ask former University of Georgia and NFL quarterback Matt Robinson. Being the quarterback of the New York Jets right after Joe Namath, brought a level of celebrity that carries on to this day.

“My brother was sitting in a bar in Montana a few years ago and heard a couple of guys talking about me down at the other end,” Robinson explained. “He walked over and introduced himself and tells them he’s my brother. The guy said, ‘My dad is such a big Jets fan he named me and my brothers after Jets quarterbacks. I’m Matt.’ My brother is absolutely dumbfounded and gets me on the phone. I talk to the guy, and eventually I talked to his dad. I still have his number.”

So, what’s that like when you’re such an idol that people are willing to name their kids after you?

“It was flattering, and sometimes I would chuckle because I never thought of myself in that way,” Matt explained. “But it was also a reminder that you never know who, or when somebody’s watching you and knows who you are.”

When I first met my friend Brooks more than thirty years ago, I casually asked him if he was named after Brooks Robinson.

“I am,” he said with a laugh, explaining that he was asked that pretty often. “My parents lived in Maryland before they moved to Jacksonville Beach. My dad was a big sports guy and quite an athlete. I was the only one of three brothers who played sports, so they gave the right name to the right son.”

Brooks said he didn’t feel any special responsibility to Robinson but did get to meet him at a golf tournament in Ft. Meyers a few years ago.

“I followed Brooks when I was young, but I played first and he played third,” he said. “I did think as an adult it was unique that he played for one team. You don’t see that much anymore. When I got to meet him and told him I was named after him he couldn’t have been nicer. He asked, ‘Do I know your family?’ with a smile. We had a few laughs and he insisted we have a picture made together.”

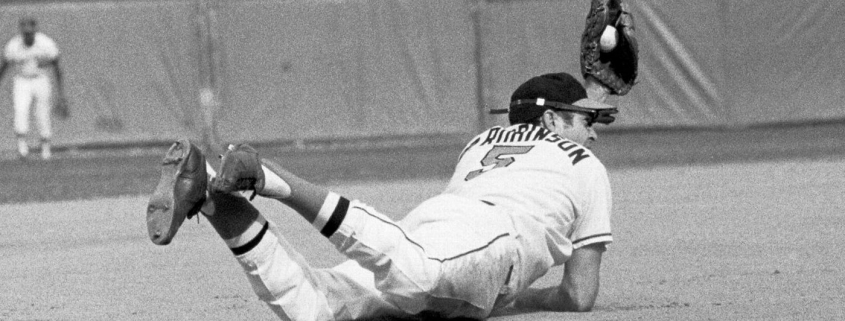

In the ‘90’s Brooks Robinson was in town for a book signing in Mandarin. I had arranged with his publisher and the store manager to be there to interview him when he was done for a story in that night’s sportscast.

The line was around the building when I got there, surprising since Brooks hadn’t played in twenty years. I walked to the signing desk and waited to the side for him to finish. Since it was before September 11th, there was no TSA checkpoint at the airport and while Brooks was signing he was asking the organizers how long it would take to drive to the airport to make his flight. He wanted to sign until the last second.

I had met him a few times before, but somebody must have prepped him as well because when he looked up, he said, “Hi Sam,” and went back to signing adding “We’ll only have a minute when I’m done, I hope that’s OK.”

“No problem,” I said.

There were still over a hundred people in line when Robinson, apologetic and disappointed he had to disappoint so many people, put his pen down and walked to the back of the store motioning for me and my photographer to follow.

He stopped at the door of the waiting car and answered a couple of questions politely, apologized and slid into the back seat. As he did, he noticed the Orioles hat I had in my hand. Without a word as the car started away, he grabbed it, closed the door and was headed to the airport.

I had a laugh about it with my photographer and the store manager and said something silly like, “Guess Brooks needed an Oriole hat!”

A few days later the manager called me to say she had received a package with my name on it. I went to the store to pick it up and when I opened it, there was my hat, signed by Brooks, with a note from him apologizing for having to “run off so quickly.” He also included a picture signed personally to me.

I often think about how I idolized Brooks when I was a kid and the formative impact, he and Frank and Wes and Johnny and Lenny had on me growing up.

Along the way I eventually realized I couldn’t hit like Brooks, and I might have been the half the fielder he was. But as an adult I’ve often thought I could still follow his example and be as kind and as gracious as he was that day.

I hope I never forget that.