The Masters is Emotional

They played early at Augusta National in yesterday’s final round of The Masters because of weather. But it didn’t make a difference. Early or late, it’s the same.

Because this is The Masters.

It was a leaderboard fitting of The Masters with Major Champions trying to add to their collection and others trying to make the Green Jacket their first Major Championship trophy. Brooks Koepka was looking for his fourth Major in the last two years and Francesco Molinari was playing well enough to add to his Open Championship win of 2018. Tiger Woods was in position to win his 15th Major and his fifth Masters.

And that’s what happened. Tiger outlasted the competition, played steady when others faltered and stood on the 18th green as The Masters Champion for a fifth time.

There was pure emotion coming from Tiger as he dropped the final putt to win by a shot. From not knowing if he’d play golf again just 18 months ago, Woods completed an improbable comeback and said later he didn’t know what he did as the last putt dropped. He just let it all out. The emotions of the week and the last two years.

And The Masters is all about emotion.

Before the traditional Green Jacket ceremony in the Butler Cabin at Augusta National today, CBS ran a montage of players over the years reacting to a question about winning the Masters. The response is universal, a long exhale with a faraway look in their eyes. It’s enormous from a golf standpoint. A major championship, endorsements and a signature win.

“I never allowed myself to dream this big,” Bubba Watson said, choking back tears.

“It’s a week not like any other week,” Andy North a two-time US Open winner told me last Wednesday.

Winning the U.S. Open is an achievement. Much is made of the qualifying process and the USGA’s protection of “par.” You’re the best player in America as the U.S. Open champion.

At The (British) Open Championship, they declare you the “Champion Golfer of the Year” and from an international standpoint, no title is more recognized. You beat all-comers.

The PGA is an accomplishment, winning among your peers, almost a throwback to the days when not every best player turned pro and played what became the PGA Tour.

But this is the Masters. And it’s different, it’s emotional.

It’s the only major that’s played on the same golf course every year. In fact, it might be the only significant sporting event that uses the same venue annually. The World Cup travels, so does the Super Bowl. The Daytona 500 is always at Daytona, obviously, but it’s stature and appeal outside of NASCAR fans is limited.

In the few minutes after sealing his victory, Tiger hugged his caddie, Joe Lacava, shook hands with his fellow competitors and caddies on the green and then went through a series of long, emotional hugs with his children, his mother, his girlfriend and other close associates.

It’s the kind of scene only found at the Masters.

When the Augusta Invitational started in 1934, it was an idea that Clifford Roberts and Bobby Jones had to bring together the best players just as the weather began to break in northern Georgia. Writers traveling from baseball spring training in Florida would find it convenient to stop off in Augusta to cover the golf. Editors in the northeast weren’t put off by the stopover, as there was limited extra expense.

Horton Smith’s win in ’34 wasn’t overly celebrated. But as is widely know, Roberts and Jones understood that putting on a golf tournament and having people know about your tournament were two different things. Through the reporting of the iconic sportswriters of the time the Augusta Invitational became The Masters.

Employees of what is now CSX in Jacksonville stood on Washington Road in Augusta outside of “The National” selling tickets. They operated the Butler Cabln as a hospitality venue for years.

Herbert Warren Wind dubbed the 11th, 12th and 13th at Augusta “Amen Corner” after a blues tune he knew from the ’30’s. Gene Sarazen’s double-eagle gave some mystery and verve to the tournament as eyewitness accounts were reported breathlessly by the major newspapers of the era. Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson and Sam Snead playing and winning showed it was important.

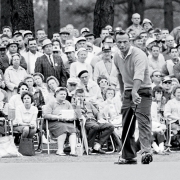

But it wasn’t until Arnold Palmer showed up and started winning did it get emotional. That’s how Palmer played and he transferred that emotion to Augusta National and the Masters.

Although he won four times, it’s the near misses that are as easily remembered in Palmer’s career at Augusta and the emotion those evoked. As television emerged as a vehicle to bring golf to the masses, TV executives like Frank Chirkinian of CBS knew Arnold was telegenic and projected that emotion right through the screen and into our living rooms. (By the way, Chirkinian also invented the “under” or “over” par scoring for television we still use today.)

And it didn’t hurt that TV could bring beautiful pictures of a golf course to the millions still saddled by snow and bad weather throughout the country.

As Jack Nicklaus emerged as the best player, the emotions at the Masters still centered on Palmer as the crowd favorite. He brought a visceral connection among the fans at the Masters as he tried to hold off the then unemotional and methodical Golden Bear. Unlike previous golf “rivalries” where you had your favorite and were polite to their competitors, Palmer fans didn’t like Jack and let everybody know. Arnold evoked an emotional response even when he didn’t win.

I say Nicklaus was unemotional, but Jack burned with a competitive fire that centered on winning and beating Palmer. He didn’t show it much, that wasn’t his personality, but being around the two it was obvious they had a deep friendship but also a competitive nature that never abated.

Until recently, Jack was the most un-sentimental champion I had ever met. Even when he won his sixth Green Jacket in 1986, it wasn’t until 20 years later that Jack started to embrace the emotion of Augusta National publicly. Tom Watson is kind of the same way. Johnny Miller once said, “Golf champions aren’t chummy,” and maybe he’s right. It’s such an individual game that it breeds and inner strength among the best players.

Sometimes the emotions of nearly winning are equal to those of winning. It’s so demanding as a golf course and as a competition and it is such a big deal that the best players of their era sometimes just don’t win at Augusta. Ken Venturi, Tom Weiskopf, Greg Norman, Tom Kite, David Duval, Ernie Els and others are supposed to be Masters Champions. Their runner-up finishes are legendary.

Art Wall, Doug Ford, Gay Brewer, George Archer, Tommy Aaron, Charles Coody, Larry Mize, Mike Weir, Charl Schwartzel, Trevor Immelman and Danny Willet, distinguished players, but not household names, even in the golf world, have Green Jackets.

Winning the Masters brings an emotional response not seen anywhere else.

Ben Crenshaw cried both times he won. Phil Mickelson shed a tear in his wife Amy’s arms standing on 18 at Augusta. Sergio Garcia dropped his face in his hands after beating Justin Rose two years ago. That doesn’t happen at a regular tour event or even the other three majors.

But this is The Masters. It’s emotional.

Either way, the Jaguars offseason moves have started with keeping the top brass and firing four assistant coaches, all in positions that underperformed this year.

Either way, the Jaguars offseason moves have started with keeping the top brass and firing four assistant coaches, all in positions that underperformed this year.